| Chez Damier: A work in progress KMS, The Music Institute, Prescription: The Chicago legend has been through it all, but if his recent activity is any indication, he’s not done yet. In this in-depth interview, Chez Damier talks about his past, present and future with RA’s Dave Stenton.

Along with a couple of friends, Chez Damier opened The Music Institute in Detroit in the late ’80s. Every nascent music scene needs an outlet. And The Music Institute proved just as important for the development of techno in the city as The Warehouse and The Music Box had been for house music in Chicago a few years earlier.

Damier, AKA Anthony Pearson, could have stopped there, assured of a place in dance music history—albeit just a footnote. But, instead—and after a few years managing the KMS studio and label for Kevin Saunderson—he returned to his hometown of Chicago and, alongside Ron Trent, created a musical legacy deserving of an entire chapter. Between 1993 and 1995, the first 15 releases on the pair’s Prescription label—widely regarded as one of the finest house imprints ever—crafted the blueprint for what would become known as deep house. And 15 years later the tracks they created together as Chez N Trent—most notably “Morning Factory,” “Sometimes I Feel Like,” “The Choice” and “Be My”—remain unparalleled examples of the genre.

When seemingly at the height of their powers, however, musical differences put paid to the partnership. Trent took sole control of Prescription and, for a year or so, Damier focused on the sub-label, Balance, before taking an extended break from the music industry. A handful of releases in 2004 and the odd DJ date hinted that a return was on the cards. But conclusive proof only came in 2009 when Damier committed to a series of releases for the German label Mojuba, as well as launching his own new project, Balance Alliance.

RA spoke to Chez prior to his recent DJ appearance at new London party, Lost In The Loft. The conversation covers his early clubbing experiences in Chicago, the development and subsequent breakdown of his relationship with Ron Trent and how, after so long out of the game, he is coping in an industry that has undergone widespread change.

You had a pretty early start in the music industry, working part-time in a Chicago record store from the age of 11. When did you first start experiencing the city’s clubs?

At age 13, which was 1980 and ’81.

Let’s focus on that period. What was it like?

Most of my experience came from people who were behind [the bigger names in terms of status]. I was taken [to clubs] by a lot of people who were artists, fashion designers, hair stylists, DJs like Craig Loftis who was behind Frankie Knuckles. I would cut his hair every Friday [so that’s how we became friends] and it was a really, really wild start for me. In Chicago, the difference between how we see house music now and then is that it was a lifestyle then.

Much more like hip-hop?

Exactly, [you could tell us] by our haircuts, by our clothes. We went from preppy to house. It was almost like that whole thing of being identified, you know, with the really pretty girls, the guys with their haircuts, you know, fashionable? So, for us, it was a culture. We really looked forward to going out—from the high school arena through to the more underground arena—we really looked forward to going out to this event, it was [just] our nature.

But I often find myself questioning people’s experience [of that period]. Although I don’t claim to be an expert I can literally say that I’ve witnessed quite a bit. And when I say witnessed I don’t mean hearsay, I mean that I was actually there. I hear some stories and some people’s interpretation of it and I think, “That’s all wrong.”

Here’s the challenge. We’re sitting facing one another. So it’s impossible for us to see the same thing. But we’re in the same room! We can agree we’re in the same room. We can agree that we’re seeing some of the same things but we cannot say that we’re seeing it from the same angle. And so this is what I have a problem with when it comes to most of the articles and documentaries and other things that I read [about the history of house music]. I think, “Yes, OK, you’ve added [some] value but that was [only] one perspective of it.” But what you don’t know is that there’s a whole other perspective on it.

People seldom mention Herb Kent who, to me, was the father of it all. He was the one that could play disco at the same time as the B-52s and totally educate me—I didn’t know who the B-52s were [before that]—who can give you punk rock and disco and Italo all in the same breath. These were the people that changed my life. [But people] want to say, “It came from this kind of underground black gay club,” which is not a problem—and I’m not taking anything away from that—but there was always something parallel happening. And when I went to the white gay clubs that were promoting the British invasion: The Thompson Twins, the whole Sheffield sound as well as Italo [disco]. And these other urban kids were also experiencing that, but they were combining it with disco and [putting] their interpretation on it. So I get so confused when I get into the whole [history of it].

Chez Damier and The Music Institute Chez Damier and The Music Institute

The Music Institute opened in 1987. It was me, Alton Miller and George Baker. We were all 21. We were motivated by Chicago and New York—and the lack of [comparable clubs in] Detroit. So, here I was from Chicago, George had just come from FIT [Fashion Institute of Technology] in New York and so he was experiencing the Paradise Garage; I had experience of the Warehouse [in Chicago]; and we both kinda got to the Detroit scene and it was all about how do we reproduce this feeling [that we had experienced in other cities]?

What a lot of people don’t know is that the Music Institute would originally have been called The Gate, and would have been at another location in Detroit, on the college campus. That building was an old automotive garage and we found the building and it had a ramp that went up to it, and George was so inspired by New York that he said, “This is so Paradise Garage, this is what we gotta do,” and so we got the place and started renovating and it was all exposed brick and we found that we were gonna need a boiler system.

So we lost [that venue] and had a short time to find another place. [Then] we found the owners of the Music Institute building and they were willing to work with us for little or nothing. It was a four-story building and [although] we [only] used the first two floors we had the whole building. It was unoccupied in downtown Detroit and we went there and made a proposal and, from that point, it was just friends of ours [who] loaned us money. The music store [also] loaned us the sound system so we were really, really fortunate.

We had a party right around the corner before it opened called Back To Basics but we didn’t see the kids that we wanted to see [at the party] because Detroit was very segregated into white, black, straight and gay. But George and I, because we were very cultured, we wanted the international combination crowd ‘cos we never saw it [in Detroit]. So we did a party and said we were gonna salute some of the great DJs. And we were hoping that the Ken Colliers, Larry Levans—all these DJs who we had [referenced] on the flyer—would draw people who had heard of them. And it worked. And it was a packed party and we went all the way to 6 AM. And that was it. We were saying, “We’re here, let’s go for it.” And that was really the pushing point. Also, when we opened it, it just so happened that techno was hitting the first wave. And we worked [the bookings] out so that Friday nights—with Derrick, Juan and Darryl Wynn, who we knew personally—were called Next Generation and Saturday, which was me and Alton, was Back To Basics.

We closed in 1989. Which is why the recent Music Institute 20th Anniversary 12-inches came out last year. They are [being released by] Kai Alce who actually at the time was a 16-year-old preppy kid who was my light boy [at the Music Institute]. He made a deal with me that if I trained him [to DJ] on Sundays he would treat me to lunch. That was the deal. We had this place that we would go to in Detroit that had all the beers from around the world and we would go there on Sundays after a DJ session and we would drink different beers from around the world. That was my pay. But I didn’t know he was underage and therefore it produced a whole other problem with his mum and that whole thing! [laughs] He lied to me and told me he was 18 years old, but he was 16.

People want a nice neat story.

But there isn’t a nice neat story! And I’ve heard the same thing about Detroit and the same thing about New York. And I can’t vouch for New York the same way I can for Detroit, but I visited Detroit about five years before I moved there and was introduced to the Ken Colliers and Greg Colliers who were the fathers of dance music [in the city] at the time and I’m thinking, when I hear stories coming out of Detroit now, and I was there at the beginnings of the Derrick Mays and the Kevin Saundersons, and what I saw and what they saw, ah, it was very different. But, again, I can’t legitimately say they didn’t see it. [All] I can say legitimately [is that] I did. How about that? [laughs]

Presumably you’ve read books like Last Night a DJ Saved My Life and seen DVDs such as Maestro and, clearly, you have some issues with them. But are any better than others in terms of telling the story of house music?

You know what? I think they all tell part of the story. But I think it’s very unfair to conclude that that is the story.

It’s not definitive.

Yeah, and that’s the problem that I have. And I’ll tell you another thing I have a problem with: people not giving [due credit to] New York and the so-called “European invasion.” To me that was the electronic music before it became house and techno. I get confused when, all of a sudden, the 909 entered into the picture, and the 808 entered into the picture and all of a sudden it’s like, “OK we [should] label this thing.” And that’s fine, but it’s almost like Columbus saying “I discovered America.” OK Columbus, you did discover America, but America was already America; you just gave it a name. And this is the problem I have with the whole rivalry: what is this and what is that? I think New York was [already] doing it underground. And Europe was [already] doing it underground. And they were doing it well because this was a generation that was coming from the disco arena and they were creating what they only knew at the time as dance music.

So the importance of Chicago and Detroit to contemporary dance music has been overly elevated?

I think it’s been more than overly elevated. I think it’s totally [out of proportion]. You know when I moved to Detroit it was about as dead as this room right now and I was partying with [both] the gay kids and the straight kids and, to be quite honest with you, there was nothing happening. The downtown was [a] ghost town. It just amazes me how [people] fight over being a “Godfather”, being a “Godson,” you know, being a “Creator.” I hate when people make it so final; to say this word is the word. So that’s why you never really hear me talk about it [definitively]. This is the first or maybe second time I’ve really been passionate about actually speaking about it because I’m at a point right now where I look back [and think] I was just a patron and, as a patron, I didn’t catch it like that. [laughs]

You became closely involved in Detroit’s underground music scene but you initially moved there to study, right?

I actually moved to East Lansing, Michigan. Funnily enough that’s where Kevin [Saunderson] and those guys were living, but I didn’t know them then. So I was there for a while and then a friend of mine who I would visit in Detroit said, “Why don’t you come to Detroit?” And I thought, “OK.” And I went down to Detroit and that changed my life forever.

How did your involvement in the Detroit underground scene come about?

Well, initially I was still trying to get into communication [at the University of Michigan] so I worked for the first pager company—beeper company—in Detroit and I came in and started working as a mobile operator. I was the guy who when the big phones—the big car phones—[first became available and people] would call from their car phone and I would patch them to [the recipient]. And working there introduced me to the security guard, Thomas Barnett. I used to have to be there early in the morning and Thomas would be the security guard overnight so we would talk. And he would say, “You know I wanna do music,” or “I’m doing music” and we got into this whole thing and I said, “Oh, you know I met these guys, and his name is Derrick, and he does music…” And I hooked them up with each other and that was the birth of Rhythim is Rhythim.

So you’d met Derrick before that?

Me and Derrick met through a friend of mine; actually it’s so strange how it happened: I met Alton Miller and Derrick May in the same week. A friend of mine knew somebody who was doing electronic music and he introduced me to Derrick and then I met Alton as they both were friends and we all just became good friends. So then Derrick introduced me to Juan and he introduced me to Kevin Saunderson.

And that was when, ’86, ’87?

’87 and ’88.

Wow, so after that it all happened pretty quickly. Were you working at KMS right from its inception?

No. Kevin Saunderson had just started it and I was attempting to work on my first [musical] project [Just A Matter of Time] with my producer at the time, Al Maalik. And so he went to Kevin, who was working on his first label, I think he had [only] done “Rock to the Beat” [at the point] or maybe “Triangle of Love,” only one or two records. Al wanted to do a compilation called Techno-1 and he introduced the project and Kevin wanted to put it out. Now that I look back on it I’m just amazed at how it happened: here I have Eddie Fowlkes recording me, here I have Juan Atkins mixing me, and here I have Carl Craig remixing me, and Kevin Saunderson executive producing me. It was just like, “Woah.” And so I’m looking back and saying, “That was really amazing.” [At the time] I was working on the Music Institute and Kevin came and asked [if I] would do some A&R for him. And that’s how I ended up [working] with him.

You did some writing for Inner City, correct? What exactly was your role?

I wrote “Set Your Body Free” off their first album: I constructed the melodies, the hook and the lyrics for the song.

Had you had any formal musical training?

None at all. I was self-taught. I hung around bands, of course, but never formally trained. I had musicians in my family but I was never really inspired by that, to be quite honest with you. I’m still not. What inspired me was that I’m very psychological so it was all about, “How do I take this feeling that I’ve experienced [on dance floors] and [re]produce it [as a piece of music].” And that’s still what happens [with me] today: it has nothing to do with how great or not I am as a musician. It’s, “How can I produce this feeling that makes me want to dance that hopefully makes other people want to dance?” That’s my whole philosophy behind it. I don’t pretend I’m some guru, or deep person, who’s studied how to do this. I’m an inspired artist; and inspired artist means simply that if I’m not inspired, nothing’s happening.

“I hate when people make it so final;

to say this word is the word.”

Ron Trent, Chez Damier’s famed production partner. Ron Trent, Chez Damier’s famed production partner.

So you were releasing records on KMS as well as managing the label and studio during the early-’90s. When did that come to an end, prompting you to move back to Chicago?

Actually, how it worked out is that I ended up moving to New York to do KMS New York and in the process of doing that we [were] just in over our heads because markets were beginning to change. So we had to close the New York office and while that was going on I came back to Detroit for a moment and, on a visit to Chicago, met Ron Trent.

How exactly did you and Ron meet?

Well there’s this guy Carl Bias, who’s largely unknown but a very intricate ingredient to the early Chicago scene. He and I were friends. And he and Ron were friends. And he said, “I gotta introduce you!” So one day me and him went by Ron’s place and that was it. From that day on it was just amazing.

And the first releases you produced together were for KMS?

Actually that’s just the way it worked out [in terms of timings]. We were preparing for Prescription at the same time. The only projects we did together for KMS were “The Choice” and “Don’t Try It.” Actually, our first production together was [a remix of] Inner City’s “Share My Life.”

What did you see in Ron, or what did you see in each other, that made you think, “We can work together”?

I think that the relationship Ron and I had was probably one of the most special, authentic relationships that anyone could ever have. There was so much excitement when we met each other. First of all the ingredient, in my opinion, which made me and Ron “me and Ron” was the laughter we had. We spent so much time laughing. Maybe we were just being silly but we would laugh about things and we had this [shared] ideology about how we heard things, how we saw it. We agreed to disagree [at times] but really it was just the laughter that made us work.

Did the two of you have prescribed roles in the studio?

Well when Ron and I met, Ron was working for Clubhouse [Records] out of Chicago and I had just released KMS049. That was our meeting point. So there weren’t actually [prescribed roles]. We came in and it depended on how we were feeling. That set the tone: Ron had his style and I had my style. I like to describe me and Ron as Ron being more laidback and me the more energy/aggressive [side of things]. So I guess, at that point, we were just trying to find a happy medium. A meeting point. And what we got was a meeting point. I think that, if you hear us individually, you can hear the meeting point; [when we were] apart from each other Ron was a fairly decent keyboardist but you can hear the difference and the energy. So when we came together that was the magic, because you had that kind of intense versus mellow combination actually happening.

Countless house DJs cite Prescription as their all-time favourite label. Did you have any idea, at the time, that the label would have such a legacy?

None whatsoever. One of the things that changed mine and Ron’s lives collectively was when I took him to New York: I took him to New York to the Sound Factory—and I think that was the first time he had been since he was a kid ‘cos I think he was originally born in New York—and we went and when we came back we ended up writing “Be My” and the whole “I Wouldn’t” project. It was just something about experiencing [the] kids dancing, [the] sound systems [in New York] that was really intriguing to us.

And Ron—if you’ve ever met him—is very into what something sounds like whereas me, on the other hand, I’m more into the feel; my signature would be the feel of the dance floor whereas I think his would be the sound of the dance floor. I don’t know [exactly] how to identify it. Sometimes you want to put a name to something to identify it. But there are some things we don’t know. I’m using this as a metaphor to try and explain that Ron had a taste of Chicago, I had my Detroit experience, and both of us went through the New York experience and so we had a little different perspective than someone who was just from Chicago, or just from Detroit, or just from New York.

You were pulling from all three equally?

Exactly. And I think that’s what made it magic for us. You couldn’t hear us and say, “That’s Chicago,” or “That’s Detroit,”or, “That’s New York.” I think if you listened to our projects you’ll hear an element of each—and even an international influence because that’s what made it work.

What’s amazing looking back is that, the first ten Prescription records, from “The Wanderer” through to “I Remember Dance,” were all released in search a short period of time. Another interesting aspect is that, aside from the logo, there’s no uniform identity—the artwork for each release is different. Was that deliberate?

Yes. It was my adventures in marketing. Even the no name thing: when I did the KMS—the no name track—I thought it was clever marketing. And [when] we came along to do the Prescription thing I thought it would also be clever marketing because I thought it was [a] way to give each release its own identity. And because it was underground we could do that. I was rebelling against the system. [laughs] The system was to conform. And we were not gonna conform. We wanted to create something. Then of course Balance [a Prescription sub-label] came out and I guess that [did] conform [to some extent].

From left to right:

PRES110: I Remember Dance

PRES000: The Wanderer

PRES101: Be My / I Wouldn’t

PRES105: Love Is The Message (For Those Who Didn’t Hear It)

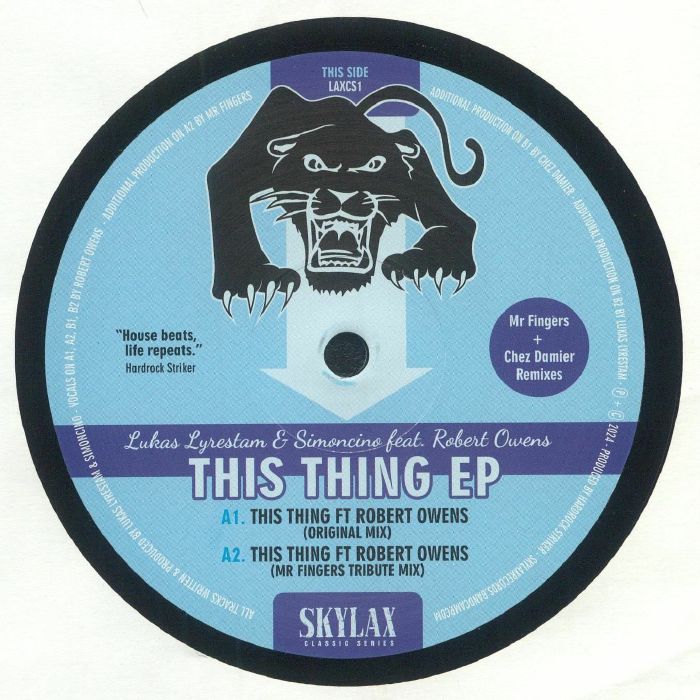

PRES107: Hip To Be Disillusioned Vol. 1

Can you pick a favourite from the Prescription catalogue?

[laughs] I can’t pick a favourite. I mean all of them have so many roots to stories. Actually, it would probably be “Be My (Friend).” Well “Love Is the Message” and “Be My (Friend).” And “Sometimes I Feel Like.” But then I have to keep on going! [laughs] But the reason for choosing “Be My (Friend)” is that was the first project we worked on after coming back to KMS from New York, so that was very, very special.

The Prescription “family” then grew to include other artists.

Me and Ron had different ideas about what the label should be like. And that would end up dividing us. I personally went to New York to spend some time with Romanthony [in order] to get the Wanderer project. That was the first Prescription. It was a way of setting the tone, of saying to people, “You know what, we’re not [just] about ourselves.” That was my intention. And since I was handling that part of what we were doing, that was my message; my message was, “I’m going to get someone”—and I knew Azuli had him [Romanthony], and I knew he had his own Black Male [label] —but I just thought that I could set such a different tone. And the version I chose of “The Wanderer” was just completely unexpected, I think. I did not want a label that [just] revolved around me. But it didn’t work out that way [in the end]. Ron would probably have preferred it to be more “us.” I didn’t. And so, to me, that was a big, big difference. So we split up and said, “OK, you take Prescription and I’ll take Balance” and, of course, then you didn’t see Balance for a long, long time. But now you see Balance coming back and what you’re going to see is the conclusion of what was intended from the start. And I think we’ve seen, from where Ron has taken Prescription, where he ultimately wanted to take it.

The split you agreed—Ron taking care of Prescription, you taking care of Balance—sounds fairly amicable. But presumably it was still tough?

We speak now. But it was a painful break-up. I’m able to talk about it now but it was a painful relationship break-up because there were so many dynamics: me and Ron lived together; we were production partners; and we also had a business together. That was a lot of each other. And we became so tight and when you spend so much time together—every day—and you travel together, it was a bit much.

We talk today and we’ve talked on several occasions about getting back together to do some things but I think I allowed Ron to be Ron and I need to be Chez right now. I’m not really in a rush to be anything [other] than me; I’m just really exercising who I am as a person and an artist. And I’m OK by that [for the time being]. When we do come together if we can still go back to the basic elements—and we still laugh with each other today—we will have something that we like.

So you’re confident you will record together again; it’s just a matter of time?

I’m fairly confident it will happen.

“My greatest fear in the world

is that people think that I

haven’t grown [as an artist].”

From 1997, when the Balance label came to an end, up until 2004, you went off the radar in terms of releases. Were you still DJing?

No.

Why was that?

Times had changed. I just had a new world that I was living. I was a soon-to-be-husband. It wasn’t about me anymore. Even more so. It just changed how I saw things and how I saw life. I mean I don’t know how many people handle things well, but here I am, as a party kid, dancing before the Knuckles and the Ron Hardys and the Dave Morales and the Farley Keiths and all these icons. And then to be a part of the revolution coming out of Detroit. I think there’s some after effects that happen [if you experience that]; I think you grow really quickly and I don’t think there’s ever really time to think about it. And I needed to [take time out and] find me in it. Before I was just kinda living it. I was on the road and living the life but I didn’t know who I was.

The music industry underwent huge changes during the ’97-’04 period when you weren’t releasing records. When you returned, how big an effect did that have on you personally?

Actually, it hasn’t [affected me]. I understand the marketplace because I’ve always been in the marketplace. It’s like a business person working in one line of business and then working in another line of business: he realises the fundamentals are the same. To me, I play the vinyl game now. But I play the vinyl game because I believe these are the last days of vinyl—and the last days could last another 100 years. But, to me, vinyl is intangibility. Vinyl says, “I was here [in] 2009.” Digital doesn’t say that. Digital says, “I have something available but, if your hard drive crashes [it’s gone].” Vinyl is like a book. Because it was never about making money in the first place, I can now have fun again doing the vinyl bit and leave the digital to those who wanna take it and make it into an empire. I have no intentions of making music into an empire.

You have two outlets at the moment: Balance Alliance and Mojuba.

The Mojuba label is the label that Chez Damier is exclusively with. Balance Alliance is the executive producer of Anthony Pearson. That’s the distinction: I don’t have to worry about Chez on Balance Alliance.

KMS recently repressed several Chez Damier and Chez N Trent releases, apparently without your consent?

How do I put it? I think it all goes back to motive: I don’t know what Kevin’s motive was. I don’t have a problem—and I let him have all the [original] proceeds anyway, I never got a dime off him, ‘cos I was loyal to him—if the motive is to launch KMS back up as a company. I don’t have a problem with that. But give us some new shit. Give us KMS 2010. Then there’s no problem. But when you do it, and you do it as a rehash, so it seems that my career is treading water, then I have a problem with it.

I guess it could impact on sales of your Mojuba and Balance Alliance releases?

I’m sure those in the know will be able to distinguish [between] the two. But I find it very disturbing. Although, on the other hand: it is promotion. So I either have to take it and make it work for me. Or I sit back and complain. So I’ll take it and make it work for me.

My greatest fear in the world is that people think that I haven’t grown [as an artist]. I don’t ever want to be at the point where people say, “He’s still where he used to be.” I don’t want to be there. I want you to say, “Wow, he’s got a different head now,” or “He’s somewhere else now.” For example, I was in Glasgow last week and people wanna talk about “when.” And I don’t even remember “when.” I’m the kinda person that, once I live it, it’s over. But people keep reminding you, “You remember ‘Can You Feel It?'” And I’m thinking, “Oh my God, that’s so not where I’m at now.” But then the other side is that I’m thankful: I have a great gratitude to them for their appreciation but I’m so far away from that [time]. Maybe some people get off on it? But I don’t. I hate anything that prevents me from growing. |